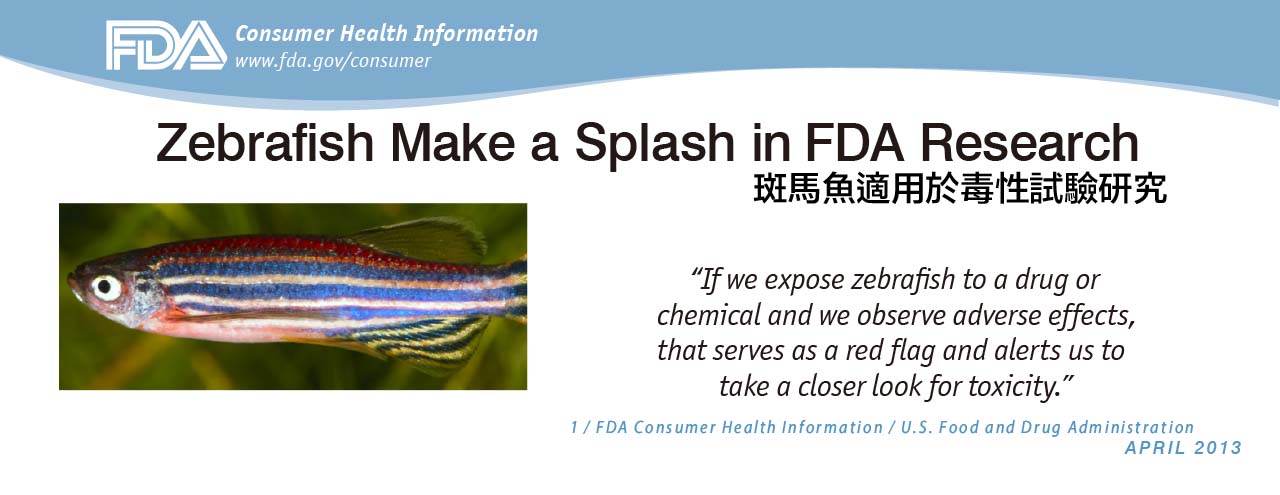

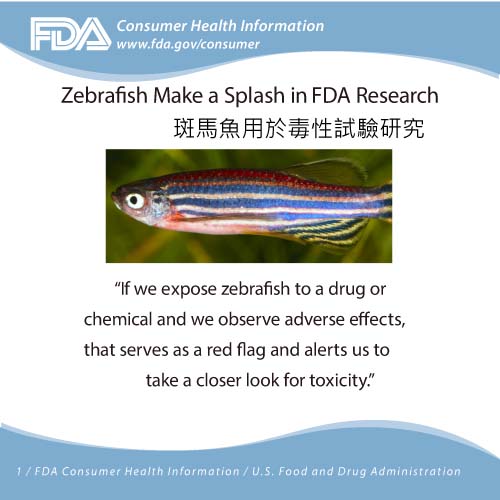

ScienceDaily (May 21, 2001) — Got Zebrafish?

Biochemists at Jefferson Medical College are using zebrafish that glow to identify potential cholesterol-processing genes. In fact, they have found a gene they’ve dubbed “Fat Free” that plays a role in controlling cholesterol metabolism.

Steven Farber, Ph.D., assistant professor of microbiology and immunology at Jefferson Medical College and the Kimmel Cancer Center of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia and his co-workers there and at the University of Pennsylvania and the Carnegie Institution of Washington, have designed special fat molecules called “optical reporters” that glow when they are cut up by an enzyme in the intestine, enabling them to watch, biochemically speaking, digestion in transparent zebrafish embryos.

The embryos are helping the scientists find genes that regulate lipid processing. By identifying the genes behind lipid metabolism, scientists are hoping to establish the basis for new and improved cholesterol-controlling drugs. Dr. Farber and his colleagues report their work May 18 in the journal Science.

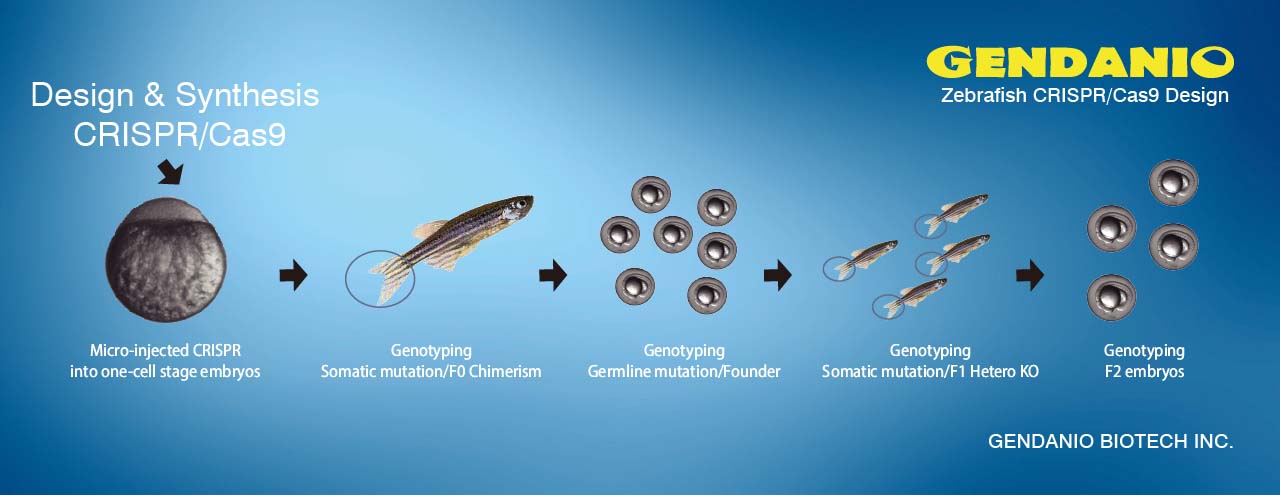

The strategy is simple: create random genetic mutations in zebrafish by exposing males to a chemical agent, then breed families harboring the resulting mutations. Each family has a unique set of mutations. The researchers then mate brothers and sisters of those families to each other. They then feed the fluorescent molecule to resulting zebrafish embryos carrying various mutations and watch it light up in the digestive tract, liver and eventually the gallbladder, examining the pattern of fluorescence. The scientists subsequently screen for alterations in lipid processing.

“A number of genes that regulate lipid metabolism have yet to be determined,” he says. “The beauty of the zebrafish genetic system is that it is an unbiased screen. We make random mutations and ask whether they interfere with lipid processing.

“We believe that we are the first to use a biochemically based genetic screen like this,” he says.

To Farber, the zebrafish is the ultimate genetic model and living laboratory. “Zebrafish are vertebrates, like humans, and abundant, accessible and optically clear,” he notes. “Zebrafish and humans have comparable lipid processing systems and more importantly, they share similar genes. In fact, nearly all human genes are present in fish.”

Dr. Farber points out that zebrafish carrying the Fat Free gene look entirely normal under the microscope and would not have been identified in a screen based on physical features, such as the intestines or gall bladder. “Our approach is to look at function, not if the organs look and are formed okay.”

One major advantage of the zebrafish model is that it allows scientists to do “forward genetics.” In this case, researchers look for a change in function, such as lipid metabolism, and then figure out what causes this effect. In reverse genetics, in contrast, researchers “knock out” a known gene and watch what effect it has on an organism, thereby getting idea of the gene’s function. The researchers tested their screen with Lipitor, a drug for hypercholesterolemia. The drug completely blocked the labeling of a fluorescent lipid in the zebrafish, meaning it halted the fish from metabolizing the optical reporter.

Drug companies are extremely interested in the research for its potential new drug targets, he notes.