ScienceDaily (Oct. 31, 2005) — Keeping the body and mind healthy depends on keeping cells healthy and functioning. This means that cells need a very robust quality-control system to repair or remove damaged or misshapen proteins. Protein handling is especially important in neurons because damage or death of brain cells causes neurological disease.

Researchers in the University of Iowa Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine have identified a protein, called CHIP (C-terminal heat shock protein 70-interacting protein), that links two arms of the quality-control machinery: refolding of misshapen proteins and destruction of proteins that are damaged beyond repair.

"For all kinds of neurodegenerative disease, from Alzheimer's disease to Huntington's disease -- which was the focus of our study -- there are problems with protein folding and protein handling," said Henry Paulson, M.D., Ph.D., UI associate professor of neurology and senior author of the study. "The protein CHIP is a key player in that process. Understanding and manipulating this pathway could lead to therapies for these diseases."

Huntington's disease is a devastating, inherited, neurodegenerative disease that is progressive and always fatal. The disease-causing gene produces a protein that is toxic to certain brain cells, and the subsequent neuronal damage leads to movement disorders, psychiatric disturbances and cognitive decline. The mutated protein contains an abnormally long stretch of a repeated amino acid and is prone to misfold and clump together, forming aggregates.

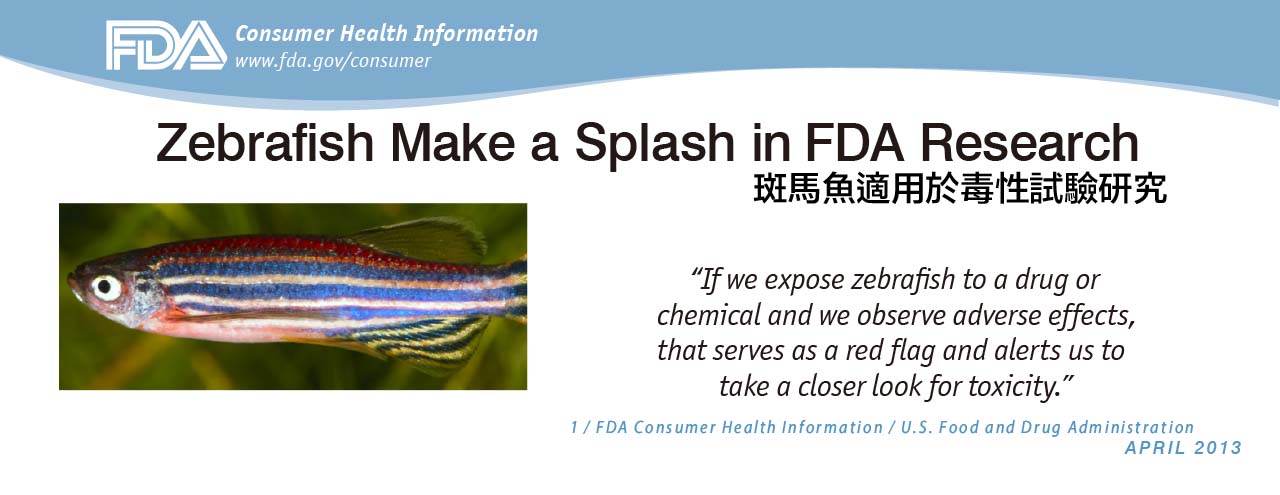

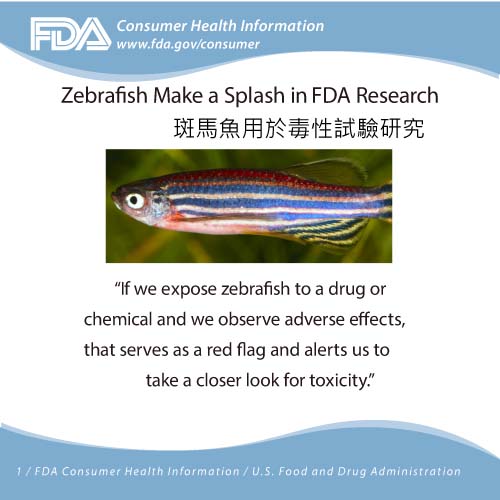

Working with several models of Huntington's disease (HD), Paulson and his colleagues found that CHIP could suppress the disease. The study, published in the Oct. 5 issue of the Journal of Neuroscience, demonstrated that CHIP decreased aggregation of the mutant protein and cell death in mouse neurons and in zebrafish. The UI team also found that in mice with only one copy of the CHIP gene, genetically engineered HD progressed more quickly and the mice died earlier than in mice with two copies of the CHIP gene and normal levels of CHIP. These findings indicate that protein quality control is disrupted in HD and also suggest that boosting CHIP 's action may be a route to potential therapies.

Paulson noted that in addition to showing that CHIP may be a good therapeutic target for neurodegenerative diseases, the study also demonstrates that zebrafish can be a powerful model for human neurodegenerative disease.

Zebrafish, a common tropical fish, have several attributes that make them attractive as lab animals. Unlike mammals, the fish embryos develop very rapidly outside of the mother and the early embryos are transparent allowing researchers to see internal development in the living creatures. Also, zebrafish are easy to manipulate genetically.

"For something that looks so unlike a human being, zebrafish share many genetic similarities including in the brain," Paulson said. "Zebrafish can be a very powerful animal model to study how genes influence and cause disease, including neurodegenerative disorders."

In addition to Paulson, the UI team included Victor Miller, a graduate student and lead author of the study, Rick Nelson, Cynthia Gouvion, Aislinn Williams, Edgardo Rodriguez-Lebron, Ph.D., Scott Harper, Ph.D., Beverly Davidson, Ph.D., the Roy J. Carver Chair in Internal Medicine and UI professor of internal medicine, physiology and biophysics, and neurology, and Michael Rebagliati, Ph.D., UI assistant professor of anatomy and cell biology.

The study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Ataxia Machado-Joseph disease Research Project and the National Ataxia Foundation.

Sorce: ScienceDaily