- By Ben Paynter

該 Email 地址已受到反垃圾郵件外掛保護。要顯示它需要在瀏覽器中啓用 JavaScript。 - November 1, 2011 |

- 12:30 pm |

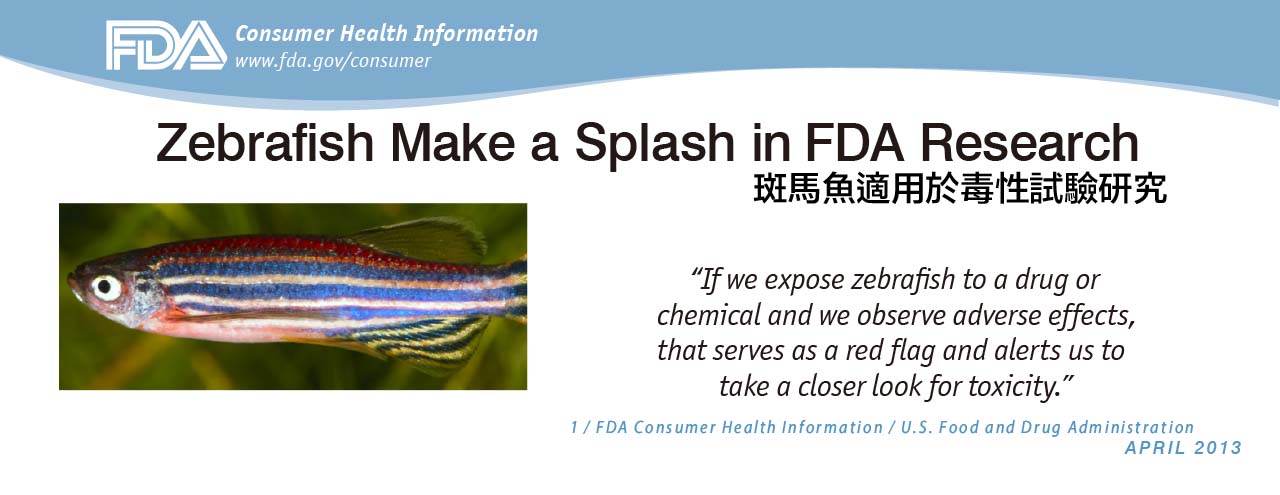

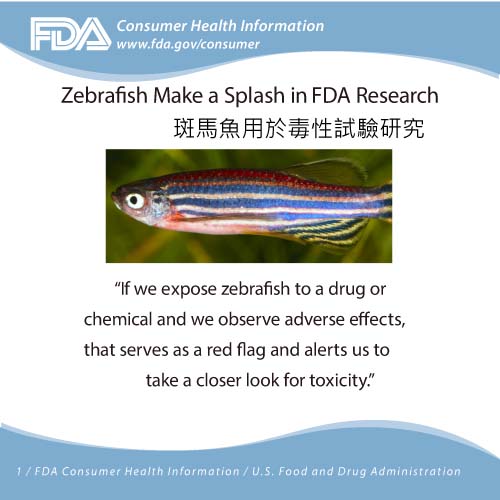

- Wired November 2011

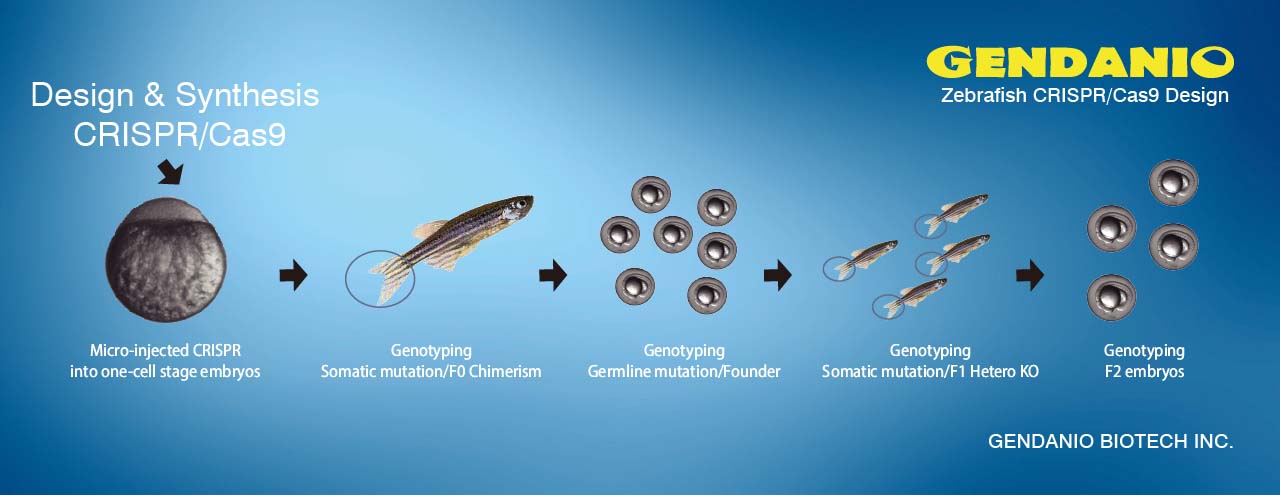

When Seattle Children’s Research Institute opens a pediatric research wing this winter, it will skip rodents to stock a better lab animal: the Danio rerio. That’s the zebra fish, a striped and translucent floater commonly sold for a buck at pet stores. Sure, fish can’t jog on a tiny treadmill or navigate a maze. But biologists at the University of Oregon discovered decades ago that the swimmers mimic human physiology pretty well. Didn’t know you had so much in common with a pet store fish? Their genetic makeup and embryonic development are similar to ours. Plus, they lay transparent eggs by the boatload. Unlike with mice, researchers don’t need to perform dissections to study fetal development—they can just zoom in with a microscope to track growth from single-cell embryo to hatchling. And because the gestation period is days instead of weeks, tracking generational shifts is easier, too.

“A lot of work in this area has been done in mice, but this is a much quicker and inexpensive way to answer some of the same questions,” says Ida Washington, director of the Office of Animal Care at SCRI, who hopes gene manipulation in embryonic fish hearts might ultimately teach researchers how to fix malformed organs in human newborns. More and more specialized strains of zebra fish are becoming available all the time: The Zebrafish International Resource Center estimates that by 2014 it will have 5,000 boutique variants available, up from 1,380 today. Wet labs at the University of Oregon are looking at what fish synapse formation can tell us about autism. Other researchers are using zebra fish to study gene therapies for cancers and to develop disease degeneration models for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Not a bad bioscientific splash for such a little fish.

Source: www.wired.com