Jim West is standing on the shoreline of Elliott Bay. To his left a huge ship is filling up at a grain terminal. To his right a cruise ship is docked at a nearby pier.

But as a scientist with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, West is not here to look at boats. He’s here to look at mussels. So we clamber down the black slippery rocks to the water’s edge.

"You can see on the underside of this rock are the black mussels and what we do is we come down here with sampling equipment and we’ll pick this off the rock, put about 150 in a bag, they get put on ice and sent to the lab."

Beside West, Alan Mearns is crouched down among the rocks, scraping off mussels. He’s a senior scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration here in Seattle and has been studying how oil impacts nature for over 30 years.

In the early 1980s Mearns helped start a program called National Mussel Watch. Since then, mussels and oysters have been regularly collected at about 300 sites around the country, including right here in Puget Sound.

Samples of the flesh of these filter-feeders serves as a snapshot of the contaminants in the surrounding water.

Mearns says that here in Washington, Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons – or PAHs are a contaminant of concern. “The levels of contamination by PAH, which are the most toxic form of contaminants in oil, is fairly high on any given day, compared to elsewhere in the United States.”

“Fairly high” is an understatement. The levels of PAHs in mussels in some parts of Puget Sound have been shown to be higher than anywhere else in the country - higher than the port of Los Angeles or San Francisco Bay - because we’re situated quite a ways inland from the flushing of the ocean. That makes the water residency time in the main basins of Puget Sound longer so organisms have a greater risk of exposure to contaminants over a longer period of time.

So where are the PAHs coming from? It would be easy to point the finger at the nearby cruise ship or the large tanker pulled up at the grain terminal next to us, but the problem is more complex than that.

These chemicals don’t just come from spilled oil or leaks at the local marina. They come from our tailpipes, our chimneys, our trains. When you burn fossil fuels, particles containing PAHs are released and they eventually get washed into Puget Sound.

In fact, up to a ton end up in the Sound every year. That’s according to a report from the Department of Ecology.

Mearns and West use the mussel tissue as forensic evidence. They’ve learned that the majority of the PAHs come from burning fossil fuels, not oil spills.

Scientists aren’t exactly sure how eating shellfish with these chemicals in them affects human health, but they’ve learned some disturbing things about how PAHs affect fish. Jim West has been monitoring PAHs in English sole, a common fish here in Puget Sound and says that PAHs my causing liver disease in these fish.

"It’s pretty gross when you see it. The liver looks like a chocolate chip cookie. It’s got a bunch of dark cancerous tumors in it. It affects their health. It effects the reproduction, they don’t reproduce as well when they have this disease."

Fish that are exposed to PAHs may have more than liver and love problems to look forward to.

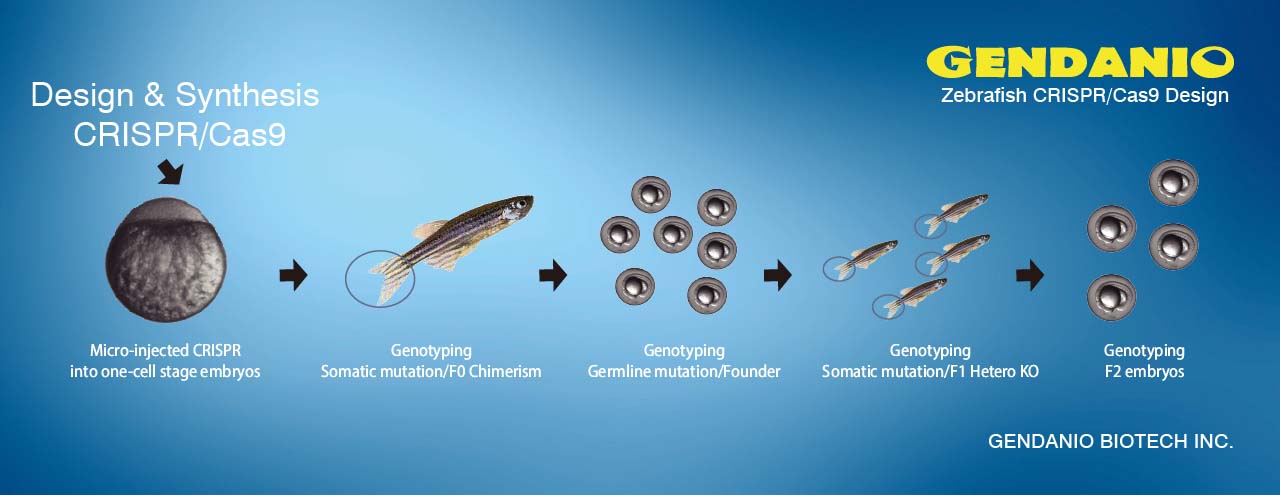

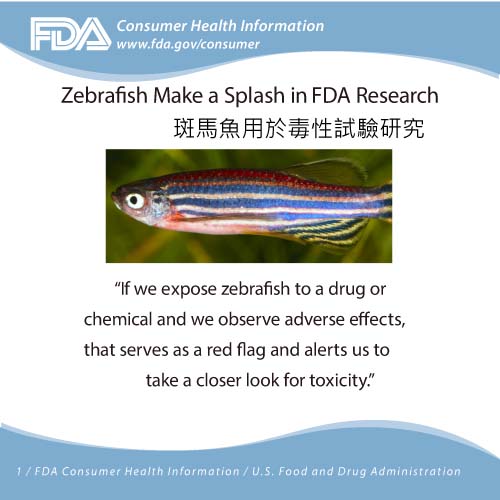

In a lab at NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Seattle, John Incardona is peering into a microscope at zebrafish embryos.

First he points to an embryo that has not been exposed to PAHs. The heart’s beating at about the same rate as a human heart, moving blood rhythmically from the atrium to the ventricle.

Then he points to the embryo that was exposed to PAHs. The heart’s bigger, he explains, because it’s dilated. “Even in humans, when someone has a failing heart the heart dilates because it’s having all this blood returning to it and it can’t pump it out fast enough.”

And as the heart swells it bumps up against the embryo’s jaw, making it develop abnormally. Incardona says many of these exposed fish die in the larval stage because their deformed jaws make it hard for them to eat.

So at low doses, PAHs aren’t lethal to zebrafish, but they can change the way these fish develop, and that can affect them for the rest of their lives.

To better understand that, Incardona puts the older exposed fish in a tube filled with flowing water — sort of like an underwater fish treadmill. The zebrafish that are exposed to PAHs can’t swim as fast as the non-exposed fish.

The trouble, Incardona says, is that this isn’t just true for zebrafish – which don’t live in Puget Sound. It’s also a problem for the home team.

“Salmon embryos exposed to oil, 6-9 months later they have reduced swimming speed and you can see that oil exposed fish have a differently shaped heart.”

These problems have also been observed in herring.

It’s tricky to get a handle on how PAHs are affecting wild fish population numbers but Jim West of the Department of Fish and Wildlife says he’s concerned about this family of contaminants, even at low levels.

“It’s really rare to see a bunch of dead fish washed up on the beach because of these contaminants unless you have an oil spill. We’re concerned more about these sublethal effects that effect their fitness or their ability to survive in the wild.”

West says that as the population of this region increases so will our fossil fuel consumption. More cars, more boats, more homes to heat could mean more PAHs and more sick fish.

This report is the second in an occasional series on oil in the Pacific Northwest.

© 2011 OPB

Source: OPB News